• ‘Reflections on a lake’ •

Landscapes need to have depth to be effective. Layering them is the key.

Click image to view large.

“‘Reflections on a lake'” By Netkonnexion on Flickr ![]()

Everybody loves an autumnal landscape.

Come autumn we are all making great images of the colours and the changes. To be successful a landscape has to look like it has some depth. In this post we are going to look at the simple way to impart depth to a landscape.

Layers

The easiest way to create depth with a landscape is to trick the eye. You are not trying to defraud your viewer. You are simply convincing the eye there is more than two dimensions. This is easy to do because your eyes expect to see depth. What you need to do is to enable the eye to actually pick up significant markers that would lead them naturally into a landscape.

There are lots of markers that you can use in composition. In fact in Easy introduction to ‘visual elements’ in photographs we identified lots of compositional markers called visual elements. When you compose a landscape using layers you are working with lines that create the markers for depth. The lines themselves are visual elements in the picture. They create boundaries for the layers in the picture.

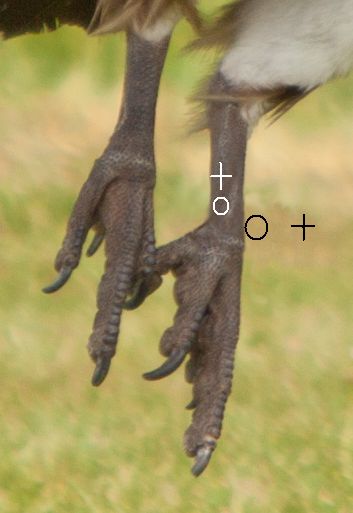

The example picture above is chosen for its simplicity. In the immediate foreground there is a patch of rock strewn grass. Not of great interest in itself, but it provides two elements. The larger boulder provides a bit of interest drawing the eye into the picture. It also seeks to divide the picture providing a visual balance either side. I will come back to this later.

The grass-lake boundary is the first line we cross. It is a major visual element in the scene. Its existence creates the foreground layer out of the grass and marks the mid-ground layer as the lake.

The lake itself is the central interest. In this picture it’s also the mid-ground layer. Great reflections always draw the eye. Then, on the far side of the lake is the next significant element/marker – the far lake shore line. This is the demarcation for the background layer – the trees. It is where the reflections originate.

The three landscape layers, foreground, mid-ground and background create depth. As the eye, in 100ths of seconds, penetrates the picture your eye/brain system sees the lines marking the boundaries of these clear zones. Immediately, the visual elements become markers for the eye to measure its travel into the picture. Depth has been established. You now see into an image, rather than at a picture. Visually creating layers in your composition, like these, will impart depth to your landscape shots.

More after this…

What’s next?

Once the eye/brain system has seen depth it remains in the minds eye. Of course if you want to sustain the viewers interest you have to find other things of interest. In this picture there are other ways the eye works through the image. The colours and tonal range are important, especially in autumn. The eye loves reds and russets. So that helps, as does the eye working to sustain an interpretation of the reflections. The ‘principle‘ there is the visual harmony between the reflections and the background layer.

Two other compositional elements control the eye. Normally a central feature of a picture, like the boulder, would draw the eye and hold it there if it was substantial enough. In this case our boulder is of small visual weight. It is not a major compositional feature, but more of a visual element (a ‘form’). You will recall from Simple ‘Principles’ of photographic composition that the ‘Principles’ control the way the eye uses the visual elements. Here the eye flows into the picture by being drawn through the middle, having established depth the eye does not go out the other side of the picture. The trees hold the eye in the picture – they form a barrier. Naturally, the eye is now drawn to cycle around the reflections. Eventually the eye will pick up the next clue.

This spot was chosen for aesthetics as well as the point of view for the shot because a central entry for the eye established the emphasis of both depth and a major point of focus on the middle ground. If you look carefully the lines that create the lake sides are narrower at the left side than the right. This funnel-effect will eventually channel the eye out of the picture on the right. The eye has a natural tendency to follow trending diagonals – no matter how slight – toward the wider ‘escape’ end. Yet, the boulder maintains a balance in overall visual terms between left and right. Eye movement is therefore under a tension to stay central as well as wishing to follow the flow to the right. This tension keeps the eye focused around the centre of the lake.

Fickle!

Yes, it is not a surprise that composition is a fickle thing. This is how I see my picture. In reality we all see it different ways. I have shown you how I rationalised the shot when it was taken. It may not work that way for you. If you have a different view why not discuss it in the comments. I would love to hear your interpretation.