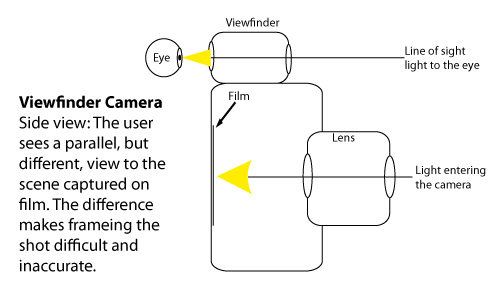

Implied lines can be created by a direction of travel of a moving object. The eye naturally moves down the line to see where the object is going. (Click to view Large).

You don’t need actual lines to direct the eye

Here is some astonishing news! You don’t even need some types of lines, for them to be effective compositional elements. Implied lines are important to help direct the eye around the picture. But they are not actually there.

Influenced by implied lines

When you look at a picture you are often influenced by the contents or some feeling or impression it gives. The influence may not be conscious. Subconscious feelings, impressions and influences play an important part in in how we appreciate and view a picture. In fact, composing a picture is the process of looking at the contents of your frame and try to find ways to make the best of your subject. In so doing you are hoping to influence the viewer and to draw them into the image, make them see something that you have picked out in your scene.

The general principles of composition with lines highlight the effectiveness of lines as a method of drawing the eye of the viewer into the picture. Possibly the use of lines is one of the stronger and more effective compositional elements. Certainly Horizontal and Vertical lines manage to provide strong leads to the way we view a picture.

Some lines in your picture do not even need to actually be there. They can be effective because they are implied lines. Perhaps one of the most common implied lines in a composition is direction of movement. When composing a picture where movement is a key component the eye naturally travels along the movement line. When you do so, you are using the implied line created by the direction of travel. A good composition will leave plenty of room in front of the moving object so it looks like it has somewhere to go – a space to move into. The implied line is then satisfied by the space.

Implied lines can be created in lots of ways. The ‘Tin Mine’ below uses a strong implied diagonal to knit the picture together. Diagonal lines are strong, dynamic, uplifting lines in composition. They promote a feeling of power. The crop in this picture, a square, creates a diagonal which intersects with all three chimneys. It also defines the left hand bottom corner of the picture. Such a strong, and yet subliminal, line is a great way to pull all the elements of the picture together creating a balance. However, sometimes it is difficult to see such a line when composing. You have to be aware that lines can be implied in order to draw on them as part of your composition.

Old Tin Mine - The implied line as a major diagonal in this picture helps knit the picture together and give an uplifting feel to the picture. (Click to view large).

Creating implied lines

There are many ways to create an implied line. Perhaps one of the most common is the line-of-sight. This is where a person or animal in the picture has a very clear fix on someone or something in the picture. The direction they are looking creates an implied ‘sight-line’. Of course there is no actual line. However, the viewer is drawn to follow the viewing line to see what they are seeing. The classic form of this is a picture of two lovers staring into each others eyes. This is a strong connection. Usually the viewer is drawn back and forth between the two people when there is such a strong correspondence between them.

Another type of implied line is to use some feature that acts as a line or pointer. In the picture below the fence points out into the lake. As it does so the viewer follows the implied line into the picture. This form of implied line is common in landscape and seascape photography.

Fences can be used to create an implied line to take the viewer into the shot. (Click to view large)

Using graphic devices like arrows painted on walls, signs on roads is another way to point in a direction through the picture. In fact almost any regular pattern which tends to follow a path but which may be discontinuous can create an implied line. Footsteps on a beach are one such example. Your eye will follow them and be drawn into the picture.

Sometimes it is easy to miss an implied compositional feature. When you compose your shot in the camera you can miss the connections between things that cause implied lines. If you are not looking for them the stones on a beach laid out by a child may point to some feature that is not your main subject. If you don’t spot them the viewer will be confused. Other potentially implied features can do the same. So watch out for things that have a connection in unexpected ways. Your composition could be made or broken by such implications.

Conclusion

Implied lines can take many forms. Mostly they are imaginary, but create a way for the viewer to be lead into or around the picture by the implication of a line. You can be creative by using discontinuous objects that together create a line. For example, footsteps or stones on a beach. Alternatively you can create an implied line by starting it off and letting the viewer keep on following the line after is has finished. Whatever you do, be aware that implied features in your picture can still convey a strong compositional impact. And, even though they do not exist, implied lines can form major compositional elements in the picture – they create a powerful impact on the viewer. Be careful that features of your picture do not create an implied line without you intending them to do so. Remember, you are in control of the composition and so you should be aware of, and in control of, all compositional elements.

Comments, additions, amendments or ideas on this article? Contact Us

or why not leave a comment at the bottom of the page…

Like this article? Don’t miss the next — sign up for tips by email.

Photokonnexion Photographic Glossary – Definitions and articles.

Principles

Horizontal and Vertical lines

Suggested extra link…

Fifteen second landscape appraisal

Damon Guy (Netkonnexion)

See also: Editors ‘Bio’.

By Damon Guy see his profile on Google+.