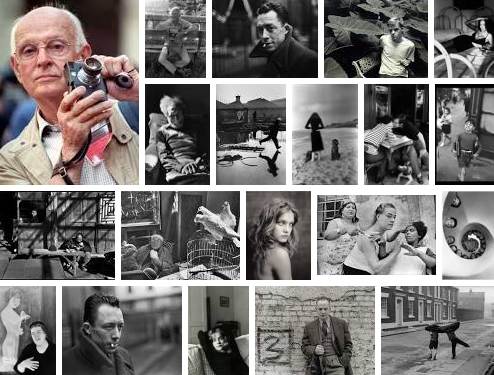

Henri Cartier-Bresson and his work.

Henri Cartier-Bresson established a tradition of excellence.

He was regarded by many as the father of photo-journalism. Cartier-Bresson was an innovator and an exceptional practitioner in photography as well as a philosopher of its essence. Here we look into a little of his life and works.

There are some great photographers doing a very poor job in the context of modern journalism. Photo-journalism has been killed by exploitation of photojournalists who are fighting a tide of bad photographs and editors who outsource on the cheap. Reportage has become commercialised and devalued by bottom-feeding organisations and journalists. Photo-journalism is however a laudable and extremely difficult pursuit. It once contributed greatly to the excellence and innovation that has given us modern photographic techniques.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (Aug 22, 1908 – Aug 3, 2004)

Henri Cartier-Bresson is recognised as pioneering candid photography, insightful timings and ‘stories-in-an-image’; disciplines in which he is still unsurpassed in many ways. A Frenchman by birth, in his early career he adopted the 35mm camera format in its infancy. Coming from a wealthy background in textiles his independent means allowed him to establish himself relatively easily. As a young boy he had a Box Brownie camera for snap shots, but he also sketched and took painting lessons from his Uncle who was killed in WWI.

In his twenties Cartier-Bresson received a classical and modernist mixed artistic education. He was fascinated by Renaissance art but remained strongly influenced by modernism. His teacher was a Cubist and attempted to mix older and modern styles. Cartier-Bresson found his teachers rule-laden approach to be too controlling. He mixed with students from other schools of art in Paris, especially the Surrealists where he was impressed with the concepts of immediacy in art.

Cartier-Bresson was frustrated by his own inability to create paintings that reconciled all his interests. He destroyed many of his early works as a result. However, many of his later ideas were matured in the mixed artistic culture of Paris at that time.

In 1928-29 he studied at the University of Cambridge learning English before completing his mandatory army service in France. While on army service he began an intense love affair which, when it ended, caused him to go to Africa to escape the obvious hurt he felt. He survived by hunting and selling the catch, but became ill and returned to Paris the adventure over. He became inspired on his return by a photograph of young black boys frolicking in Lake Tanganyika. The spontaneity and movement stimulated a sudden and inspired uptake of photography. His realisation of the possibilities of an instant story in a picture enabled him to develop the first ideas about street photography. He hunted for the reality of street life right across Europe. On his travels he met up with David Seymour and Robert Capa who both became famous photographers as well. Capa, who was already established mentored Cartier-Bresson and the three shared a studio.

As WWII broke he joined the French army in the Film and Photo Unit. However, in 1940 he was capture and spent two years in prisoner of war camps doing hard labour. A successful third escape attempt saw him returning to France to fight in the Resistance.

In 1947 Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, David Seymour, William Vandivert and George Rodger formed a cooperative picture agency, Magnum Photos. Splitting the world between them Cartier-Bresson took India and China. He went off to India to cover Gandhi’s funeral, the Chinese civil war and the formation of Maoist China. He quickly found his feet on these assignments and won wide acclaim. Magnum was established to meet and disseminate photography in the service of Humanity and to provide arresting and widely viewed images. The agency, still active today and one of the worlds most productive photojournalism organisations, became a phenomenon in a very short time.

Cartier-Bresson had worked in some of the most difficult and trying periods of the mid-20th Century, been educated with some of the most mixed and volatile artistic elements in Europe and suffered great personal hardship at the hands of the Germans. So, his philosophical approach to photography did not fully emerge until 1952. It was then that he published his first book, ‘Images à la sauvette’, (English edition titled ‘The Decisive Moment’). In it the immediacy of the Surrealists and the composition and classical rules of art came together. His idea was that everything had a decisive moment. A moment when the composition, the meaning and the expression of the cameraman all came together in a fraction of a second. He summed it up in 1957…

“Photography is not like painting. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative,”… “Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Washington Post; 1957

Cartier-Bresson retired from active photography to return to painting in the late 1960s. He had spent more than thirty years racing between some of the greatest events and upheavals of the 20th Century. His reportage was superb, his photography extraordinary. Yet he is probably best known for some tiny moments. He is my hero because in all those years of wielding a camera at momentous instants in world history his best photographs document something quite different. With the wide-eyed wonder of a child and the sophistication of a trained artist he captured some of the tiny details of ordinary lives. These were images of people who were experiencing an infinite story in a finite moment. He was simultaneously the master of the moment and the artist of the event. He hunted, as a professional photographer, for the one moment that made an impact and thereby documented a microcosm.

Photokonnexion Photographic Glossary – Definitions and articles.

Learn from the insights of famous photographers

Henri Cartier-Bresson – On Photoquotes.com

Emotional Photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson Photographs on Google Images