Exposure changes can affect many aspects of an image. Colour, mood, visual impact, contrast and others. The second image below show the differences.

Image better seen large. Click image to view large.

There is no such thing as a perfect exposure

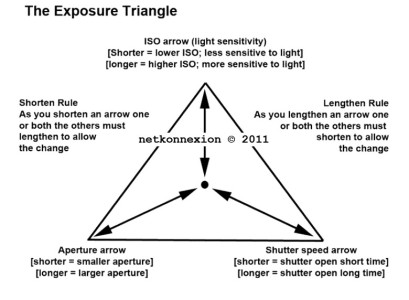

The main goal of starter photographers is to control the exposure. The Exposure Triangle, or other models of balancing light, lead learners to pursue ‘perfection’. Once they grasp the concept of balancing ISO, Aperture and Shutter speed, the needle in the camera viewfinder is their guide.

In manual mode, that central needle is important. It shows that the three elements are balanced. The unwary learner is soon overwhelmed by that needle. They have learned how to keep it central. Now they are going to keep it there despite everything. They have learned that, if the exposure changes, the needle drifts off the middle position. When that happens it is no longer “perfect”.

That mid-position needle is useful. However, it is not ‘perfection’. It is just a guide. Modern camera manufacturers have made things easy for the camera user. The technology, sensors and controls on a modern camera mislead the unwary into a false position. Complex technology and controls give the user confidence that the camera must be right. They assume the central needle creates the perfect capture. That is simply not true.

The balance of light controls the quality of outcome you want. Your final image is created by that quality of light. The creative photographer uses exposure changes to to conjure up the result they want. A good photographer commands the camera to create the picture. The camera does not create the perfect exposure for the user. The user makes exposure changes to create the desired image. Deliberate under or overexposure is an important part of creating your image.

Exposure changes allow you to command the camera

In the image below we see (almost) the same picture as above…

This second image shows same scene as above. But the different quality of exposure changes the experience of the picture. This outcome is no more correct than the top picture. However, when it was taken this one was 1 and 1/3 stops underexposed on the camera viewfinder scale. It was taken within seven seconds of the first image.

Image better seen large. Click image to view large.

I was trying to create an Autumn evening view and the deliberate underexposure gave me the key. Yes, I deliberately underexposed to create the effect. I was commanding the camera to create my “perfect” scene for what I wanted.

Experienced photogs make exposure changes regularly

For me, the darker version was right for the reasons I needed that photograph. The control of the intensity of shadows, colours, contrasts, and so on, can be done many ways.

For example, High key shots often use exposure changes. They are created by deliberate overexposure. That brings out the intense whites in a high key image.

Many portraits are lit very brightly to the eye, but a very small aperture or fast shutter speed limits the light entering the camera. This will create an underexposure bringing out the facial features. This gives shadows a depth, without harshness, as can be seen in the next image. This use of exposure changes is a great mood enhancer.

Portrait underexposed in-camera creates a tonally controlled result.

Create the exposure changes you want

How do you create this effect of under or overexposure? Simple. There is a control that can do it in auto or semi-auto modes. While in an auto-mode use the “exposure compensation” dial. You can add or subtract one or two stops of light. You can find out how to use the dial in your manual.

For the learner going fully manual it is even easier. That central needle position is your guide to what the camera calculates as an optimum light level for the shot. To create a manual over or underexposure simply dial the exposure-meter back or forward. Move the needle away from the central position. Shocking I know. You actually create exposure changes by deviating from the central needle position.

Exposure changes of one stop halves or doubles the light entering the camera. So be careful. Take several test shots. Dial one third of a stop or more at a time. Look at the result and check if you have created the right effect.

Create your image in mind – then make exposure changes to suit

The way you want your image is a creative decision. The camera should not be allowed to dictate the outcome.

You have two choices. If you go with the settings the camera gives you, the result is an optimum of the balance of the settings. If you can foresee what you want to achieve, then create your own result. In this case, make the balance of settings so the exposure changes to your choice. Your choice will be different to the result the camera would give you. But with care and practice it will be what you intend for your shot. You have taken control.

So next time you are taking a photo consider this. If you think your picture would be more effective as a darker or lighter representation, then make the exposure changes you need. Do it – create. Really make your images – don’t just capture what is there.

Comments, additions, amendments or ideas on this article? Contact Us

or why not leave a comment at the bottom of the page…

Like this article? Don’t miss the next — sign up for tips by email.

Photokonnexion Photographic Glossary – Definitions and articles.

Definition: Exposure

Definition: Exposure Triangle

Definition: Aperture

Definition: f number; f-stop

Understanding The ‘F’ Stop

Definition: Depth of Field:

Definition: ISO

Definition: Digital Noise

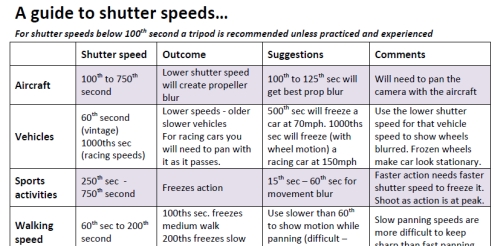

Definition: Shutter Speed

The Exposure Triangle – An aid to thinking about exposure

Definition: High key

Damon Guy (Netkonnexion)

See also: Editors ‘Bio’.

By Damon Guy see his profile on Google+.