Image files hold hidden data about the file and the image itself

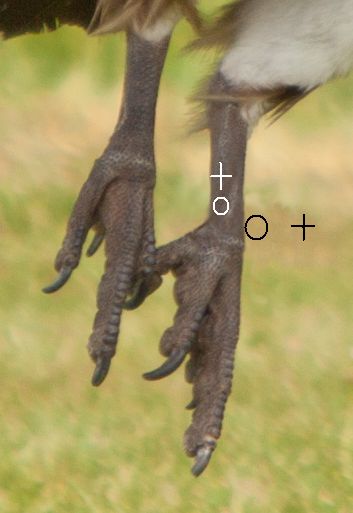

'The Kick' - image files store EXIF data about the file itself. See below for data in this image file.

Make - Canon Model - Canon EOS 5D Mark II

Orientation - Top left

DateTime - 2011:04:09 11:04:14

Artist - Damon Guy (Netkonnexion)

Copyright - Photokonnexion 2012

ExposureTime - 1/640 seconds

ISOSpeedRatings - 100

ApertureValue - F 4.00

Flash - Flash not fired

FocalLength - 280 mm

ExposureMode - Manual

White Balance - Manual

SceneCaptureType - Standard

The stored data is called EXIF. It stands for Exchangeable Image File Format. The EXIF data is stored by a number of image formats including JPEG, JPG, Tiff, RIFF and WAV files. It’s also found in many camera RAW formats. EXIF data is not supported by JPEG2000, PNG or GIF image formats.

EXIF is a great source of information. Once you understand it you can find out how the shot was make. Look at images by other people. It is an insight into the way they made a that image. When you see a picture you like view the EXIF data. You can tell from the values what settings were for that shot. Bear in mind EXIF data can be removed from a photo. So, it may not always be there.

EXIF data is a great learning aid. You can look at the EXIF data in your own image files. Check out the settings at the time your shot was taken. If the shot did not go well you can analyse what went wrong. Next time you will know better.

Getting the EXIF data

EXIF data is available in a number of ways. You can get it from most image editors when you open your file. Irfanview, an image viewer and editor, has a dialogue box for reading and copying EXIF {press ‘altgr’ & ‘e’ together}. Photoshop and Elements have read and edit tools for EXIF data. GIMP ![]() has the same facility. To use these editors to see EXIF data consult the help pages for your version.

has the same facility. To use these editors to see EXIF data consult the help pages for your version.

More after the jump…

You can also get the EXIF data using Windows Explorer…

- Windows XP: Right click the image file; left click “Properties”; click the ‘Summary tab’; click the ‘Advanced button’

- Windows Vista/Windows 7: Right click the image file; left click “Properties”; click the ‘Details tab’

- Mac OS X: view EXIF data with ‘Finder’. Do a ‘Get Info’ on a file; expand the ‘More Info’ section

In some versions of Windows you can edit the EXIF data as well as read it. However, the data about the file itself remains in the file. You can remove the private data and edit the camera data. Although you can edit the information in Windows XP it is inadvisable as a bug sometimes corrupts the data in JPEG/JPG files.

Editing your EXIF data

Data from EXIF files includes camera settings data stored when the shot was taken. There is also copyright data you can edit in-camera or add while editing.

Being able to edit your EXIF file is useful. You might want to put extra data into the file that’s not collected by your camera. For example you may want to save contact and copyright details. Or, you might want to remove some of the data. Some photographers do not publish EXIF data to prevent publishing information about the shot.

Not all cameras support all fields. The EXIF format is supported by at least the Japanese camera makers. There are many other cameras supported too.

EXIF data – many ways to use it

There are many ways to use the EXIF information. The first stage is to look at the data in your own image files.

You can also set up your camera to create EXIF data. It will store your copyright information and other data in your images when you make a photo. You can also add other types of data beyond the pure EXIF data. See your camera manual for instructions.

Have fun with your EXIF data!